Legal Shields: How British Laws Protect Endangered Sea Turtles

For millions of years, sea turtles have navigated Earth’s oceans, surviving asteroid impacts and ice ages. Yet today, all seven species face extinction due to human activity. As these ancient mariners battle for survival, the United Kingdom stands as a crucial guardian through its comprehensive legal protections.

This definitive guide examines the complex web of British legislation safeguarding sea turtles—from domestic waters where leatherbacks feed on jellyfish each summer to Caribbean UK Overseas Territories hosting critical nesting grounds. Discover how the Wildlife and Countryside Act, international agreements, and innovative conservation partnerships create layered protection for these endangered species.

Through detailed case studies from the Turks and Caicos Islands and British Virgin Islands, readers will understand how conservation policy evolves to balance traditional practices with sustainability. The article explores how British laws adapt to emerging threats like climate change, plastic pollution, and fishing bycatch while working within international frameworks for migratory species protection.

Whether you’re a conservation professional, policy maker, student, or concerned citizen, “Legal Shields” provides an authoritative roadmap through the UK’s innovative approaches to marine conservation. In an era of unprecedented biodiversity loss, this article offers critical insights into how thoughtful legislation can provide hope for endangered species recovery.

“A masterful examination of how one nation’s legal framework contributes to global conservation efforts. Essential reading for anyone interested in marine policy or environmental protection.” — Dr. Elisabeth Morrigan, Director, International Marine Conservation Institute

The Sea Turtle Crisis

For over 100 million years, sea turtles have navigated Earth’s oceans, playing vital roles in marine ecosystems. These ancient mariners face unprecedented threats today, with all seven species found globally classified as either vulnerable, endangered, or critically endangered on the IUCN Red List. As island nations with extensive marine territories and overseas dependencies, the United Kingdom shoulders significant responsibility for sea turtle conservation.

This article examines how British legislation works to protect these endangered species both in domestic waters and across UK Overseas Territories (UKOTs). Despite limited nesting activity in mainland Britain, UK waters provide critical feeding grounds for some species, particularly the leatherback turtle. Moreover, the UK’s Overseas Territories, especially those in the Caribbean, host globally significant nesting and foraging populations of multiple turtle species.

The legal framework protecting sea turtles reflects the UK’s dual commitment to domestic conservation and international environmental agreements. This complex web of legislation operates across different jurisdictions and maritime zones, creating a comprehensive but sometimes challenging system of protection. Understanding this legal ecosystem is essential for conservation practitioners, policymakers, and anyone concerned with marine protection.

As climate change alters marine habitats and migration patterns, as plastic pollution permeates even the most remote ocean regions, and as coastal development continues to threaten critical nesting sites, the importance of robust legal protections for sea turtles has never been greater. This article aims to provide a clear roadmap through the UK’s legal mechanisms for sea turtle conservation, highlighting successes, identifying gaps, and outlining future challenges.

By examining how British laws serve as shields for these endangered marine reptiles, we can better understand the role of legislation in species protection and the complex interplay between national laws and international conservation efforts. The story of sea turtle protection in the UK illustrates broader themes in environmental governance and demonstrates how legal frameworks must evolve to address emerging threats to marine biodiversity.

Key UK Legislation Protecting Sea Turtles

The Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981

The Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 (WCA) forms the backbone of wildlife protection legislation in Great Britain. Enacted to comply with the European Directive on the Conservation of Wild Birds and the Bern Convention, this landmark legislation provides protection for all species of marine turtles in UK territorial waters up to 12 nautical miles from shore.

Under the WCA, all marine turtles receive strict protection. The Act makes it illegal to deliberately kill, injure, or take sea turtles from the wild. It also prohibits possessing or selling turtles or their parts, subject to certain exceptions. Importantly, the WCA protects sea turtles at all life stages, extending coverage to eggs and juveniles as well as adults.

The WCA’s protections apply not just to deliberate harm but also to reckless actions that might disturb or damage turtle habitats. This comprehensive approach recognizes that indirect impacts on habitat can be just as detrimental to turtle populations as direct targeting.

When first introduced, the WCA represented a paradigm shift in British conservation law, moving sea turtles from being managed as a fisheries resource to being protected as endangered wildlife. This transition reflected growing scientific understanding of turtle ecology and the mounting evidence of population declines globally.

Regular reviews of the schedules listing protected species ensure that the WCA remains responsive to new scientific evidence and changing conservation priorities. The Act has been amended several times since its introduction, strengthening protections and increasing penalties for violations.

Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2017

Building upon the foundation established by the WCA, the Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2017 (CHSR) further strengthens protection for marine turtles in UK territorial waters (0-12 nautical miles). These regulations transpose the European Union’s Habitats Directive into domestic law.

Under these regulations, offenses against marine turtles include disturbance, capture, killing, and damage to breeding or resting places. The CHSR creates a more comprehensive legal framework that addresses both direct harm to individual turtles and indirect harm through habitat degradation.

The CHSR also enables the designation of protected areas specifically for marine species, though to date no UK marine sites have been designated exclusively for turtle protection. This reflects the reality that turtle occurrence in UK waters, while regular, is diffuse rather than concentrated in specific locations.

A key strength of the CHSR is its robust enforcement provisions, which allow for substantial penalties for violations. These regulations establish a clear system of permits for activities that might affect protected species, ensuring that scientific research, conservation work, and other legitimate activities can proceed while maintaining strong protections.

Conservation of Offshore Marine Habitats and Species Regulations 2017

Complementing the CHSR, the Conservation of Offshore Marine Habitats and Species Regulations 2017 (COHSR) extend similar protections to marine turtles in offshore waters from 12 to 200 nautical miles. This coverage of the UK’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) ensures that sea turtles receive consistent protection throughout British waters.

The COHSR was designed to ensure that UK marine conservation law would continue to function effectively after Brexit while maintaining consistency with international obligations. The regulations address the particular challenges of enforcement in offshore environments, where monitoring is more difficult and jurisdictional questions more complex.

Together, the CHSR and COHSR create a seamless legal framework protecting marine turtles across the entirety of UK waters, regardless of distance from shore. This comprehensive spatial coverage is vital for highly migratory species like sea turtles, which may traverse multiple jurisdictional boundaries during their life cycles.

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES)

Beyond domestic legislation, the UK’s implementation of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) provides another critical layer of protection for sea turtles. All sea turtle species are listed in CITES Appendix I, which prohibits international commercial trade in these species and their products.

The UK’s commitment to CITES is reflected in domestic regulations that strictly control the import, export, and commercial use of sea turtles and turtle products. These regulations include exceptions for pre-1947 antique items with documented provenance, recognizing historical trade while prohibiting new exploitation.

CITES implementation in the UK involves cooperation between border authorities, police, and conservation agencies to detect and prevent illegal trade in turtle products. This multi-agency approach has proven effective in addressing wildlife trafficking networks that target high-value species like hawksbill turtles, prized for their shells.

The UK has maintained and strengthened its CITES commitments post-Brexit, demonstrating continued international leadership in combating wildlife trafficking. This aspect of turtle protection addresses threats beyond UK borders, recognizing the global nature of pressures on turtle populations.

Sea Turtles in UK Waters

Species Found in British Seas

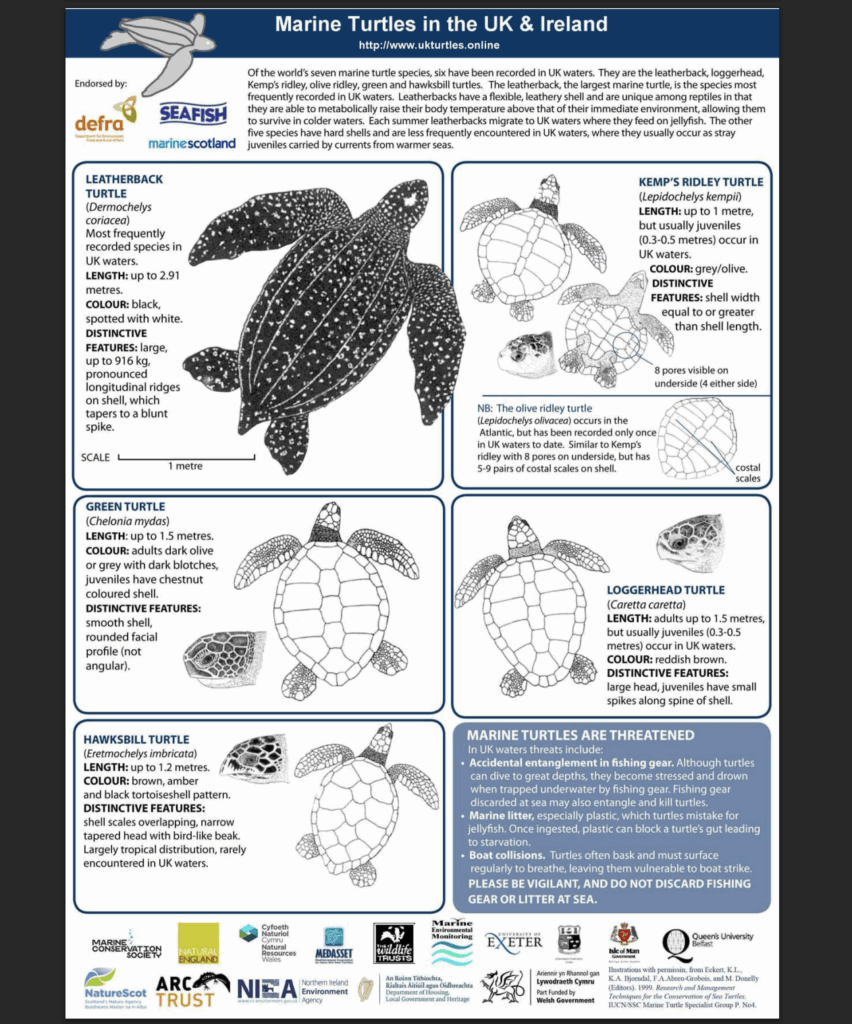

Despite being situated in temperate waters, the UK’s marine environment supports several sea turtle species. Of the world’s seven species, six have been recorded in UK waters, with the leatherback turtle (Dermochelys coriacea) being the most frequently encountered.

The leatherback turtle deserves special attention as the species most adapted to British waters. Unlike other sea turtle species, leatherbacks can maintain a body temperature higher than their surroundings, allowing them to thrive in cooler northern waters. These massive turtles—which can exceed 2 meters in length and weigh up to 900 kg—make seasonal migrations to UK waters to feed on jellyfish, their primary prey.

Other species occasionally found in UK waters include the loggerhead (Caretta caretta), Kemp’s ridley (Lepidochelys kempii), green (Chelonia mydas), and hawksbill turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata). These hard-shelled species typically appear as juveniles carried by ocean currents far from their usual tropical or subtropical habitats. In colder British waters, these turtles often become cold-stunned and may strand on beaches, requiring rescue and rehabilitation.

While no sea turtle species nests on mainland UK beaches, the country’s waters serve as important foraging grounds, particularly for leatherbacks. Recent research using satellite tracking has revealed that leatherbacks feeding in UK waters often migrate from nesting grounds in the Caribbean, including UK Overseas Territories, highlighting the interconnected nature of turtle conservation challenges.

Threats to Sea Turtles in UK Waters

Sea turtles in UK waters face numerous anthropogenic threats, with fishing gear entanglement being perhaps the most significant. Turtles can become entangled in nets, lines, and other fishing equipment, leading to injury or drowning. Though many of these incidents are accidental bycatch, the outcome for the turtle is often fatal regardless of intent.

Marine litter, particularly plastic, poses another serious threat. Leatherback turtles commonly mistake floating plastic bags for jellyfish, their primary food source. Ingestion of plastic can block a turtle’s digestive tract, causing starvation or toxic effects. Entanglement in abandoned fishing gear—known as “ghost gear”—is another litter-related threat.

Vessel strikes represent a third major threat. Sea turtles must surface regularly to breathe and often bask at the surface, making them vulnerable to collision with boats and ships. The UK’s busy shipping lanes and active recreational boating sector increase this risk, particularly during summer months when both turtle presence and boating activity peak.

Climate change will likely exacerbate these threats while introducing new challenges. Warming oceans may shift the distribution of prey species, altering turtle migration patterns. Changes in ocean currents could affect the dispersal of hatchlings and juveniles, potentially bringing more tropical species into UK waters as temperatures rise.

Pollution beyond plastic also threatens sea turtles. Chemical contaminants, oil spills, and increasing ocean noise from shipping and offshore construction all create additional stressors for turtle populations already facing multiple threats.

The UK Turtle Code

Guidelines and Best Practices

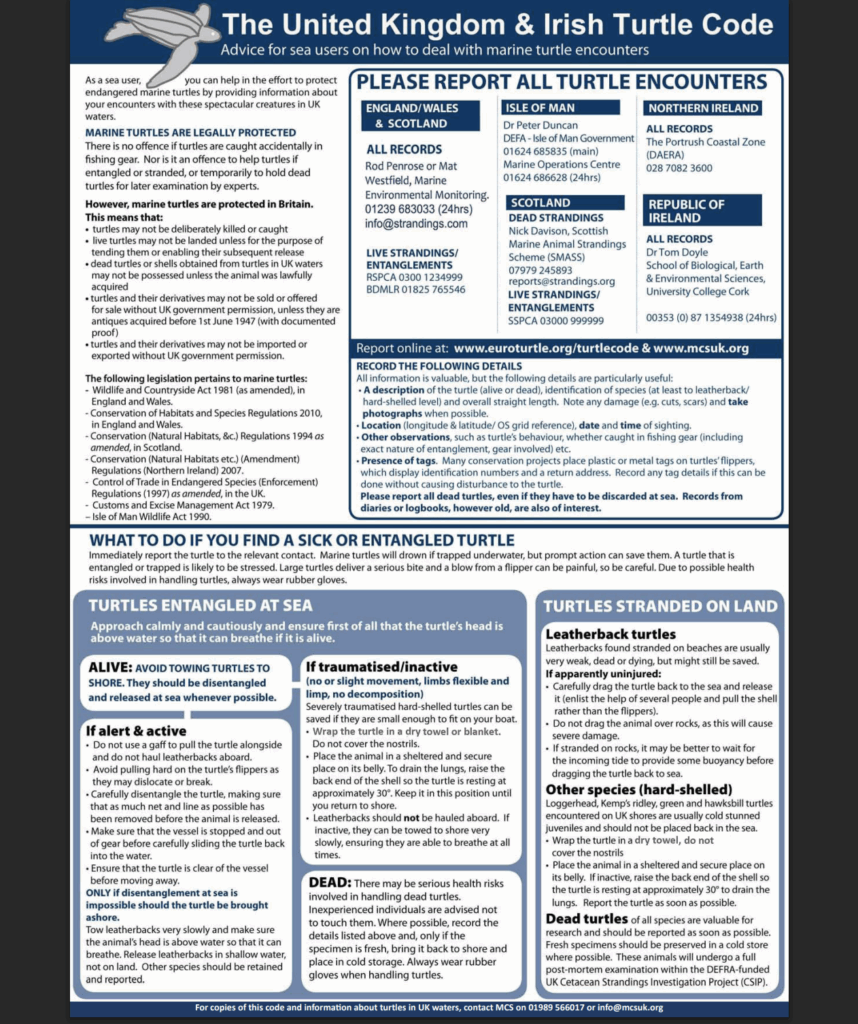

The UK Turtle Code provides clear guidelines for interactions with marine turtles, establishing best practices for various stakeholder groups including fishers, boaters, beachgoers, and conservation practitioners. This code represents a practical application of the legal protections discussed earlier, translating formal regulations into accessible guidance.

For encounters at sea, the code advises maintaining safe distances from turtles, reducing vessel speed in areas of known turtle activity, and avoiding sudden movements that might startle the animals. These voluntary measures complement legal protections against disturbance and injury.

For fishers, the code provides specific recommendations for handling accidentally caught turtles, emphasizing techniques that minimize stress and injury while complying with legal requirements. It clarifies that while accidentally catching a turtle is not an offense, certain handling and release protocols should be followed.

For stranded turtles, the code outlines appropriate first response procedures for both live and dead strandings. It provides contact information for relevant authorities and explains the legal framework governing turtle handling, possession, and research activities.

The code also addresses common questions about legal obligations, clarifying what actions are permitted under various circumstances. For instance, it explains that temporarily holding a distressed turtle for rehabilitation purposes is permitted, provided proper authorities are notified and appropriate care is provided.

By promoting voluntary best practices that exceed minimum legal requirements, the UK Turtle Code exemplifies how education and guidance can enhance the effectiveness of formal regulations. The code’s emphasis on explaining the rationale behind recommendations helps build stakeholder support for conservation measures.

Reporting and Monitoring Systems

The UK has developed effective systems for monitoring sea turtle presence in its waters, relying heavily on citizen science and established reporting networks. The Marine Conservation Society coordinates a turtle sighting program that encourages the public to report encounters with sea turtles, whether at sea or stranded on beaches.

These reporting systems serve multiple purposes: they generate valuable scientific data on turtle distribution, allow for rapid response to stranded or injured turtles, and create opportunities for public engagement with marine conservation issues. The data collected helps track changes in turtle presence over time, potentially revealing shifts due to climate change or other factors.

When live stranded turtles are reported, a network of trained responders can be activated to assess the animal, provide emergency care, and arrange transport to specialist rehabilitation facilities if needed. The UK has several facilities capable of rehabilitating cold-stunned or injured turtles, though cases requiring long-term care are sometimes transferred to facilities in warmer countries to aid recovery.

For dead stranded turtles, protocols exist for detailed examination and necropsy by qualified experts. These examinations can reveal valuable information about cause of death, feeding ecology, contaminant loads, and other aspects of turtle biology that inform conservation efforts.

Technology plays an increasing role in sea turtle monitoring, with satellite tracking studies providing unprecedented insights into movement patterns and habitat use. These studies have revealed the extensive migrations undertaken by turtles using UK waters and highlighted connectivity with distant nesting sites, including those in UK Overseas Territories.

UK Overseas Territories: Hotspots of Turtle Conservation

The Significance of UK Overseas Territories for Sea Turtles

The United Kingdom’s Overseas Territories (UKOTs) host globally significant populations of multiple sea turtle species. These territories—remnants of the British Empire scattered across the globe—often feature the tropical beaches and productive marine habitats that sea turtles rely on for nesting and foraging.

In the Caribbean region, British territories including Anguilla, the British Virgin Islands, the Cayman Islands, Montserrat, and the Turks and Caicos Islands provide critical habitat for green, hawksbill, loggerhead, and leatherback turtles. These islands support nesting populations that contribute significantly to regional turtle abundance.

The significance of UKOTs extends beyond simply providing habitat. These territories offer opportunities for implementing conservation measures with fewer of the competing pressures found in more developed or populous regions. Their relatively small size and clear governance structures can facilitate comprehensive protection measures.

From a legal perspective, the UKOTs operate under a complex arrangement where the UK government retains responsibility for international relations, including environmental agreements, while local governments often have substantial autonomy over domestic legislation, including environmental protection. This creates both challenges and opportunities for sea turtle conservation.

The UK government recognizes the global importance of biodiversity in its Overseas Territories, which host an estimated 94% of the UK’s unique biodiversity. This recognition is reflected in funding programs like the Darwin Plus Initiative, which supports conservation projects in the UKOTs, many focused on sea turtle protection.

Conservation Efforts in the Caribbean UKOTs

Conservation efforts in Caribbean UKOTs have evolved significantly over recent decades, transitioning from basic monitoring to comprehensive management approaches. These efforts typically combine scientific research, community engagement, and policy development to address the multiple threats facing sea turtle populations.

Scientific research in these territories focuses on population assessment, habitat mapping, and tracking studies to understand migration patterns. This research often involves partnerships between local organizations, UK-based institutions, and international conservation groups, creating knowledge-sharing networks that strengthen regional conservation capacity.

Community engagement has proven essential for effective turtle conservation in the UKOTs. Many territories have traditional or cultural connections to sea turtles, including historical turtle fisheries. Successful conservation initiatives acknowledge these connections while promoting sustainable alternatives and building local support for protection measures.

The Marine Conservation Society (MCS) has pioneered the use of the Community Voice Method (CVM) in several UKOTs to engage stakeholders in turtle conservation. This approach uses interviews and film to document diverse perspectives within communities, creating a platform for inclusive discussion of management options. In the Turks and Caicos Islands, this process contributed to new fishery regulations protecting large breeding turtles.

Policy development in the UKOTs increasingly reflects modern conservation science while respecting local contexts. Several territories have updated turtle protection legislation to address emerging threats, expand protected areas, or strengthen enforcement provisions. These policy changes often result from collaborative processes involving both local stakeholders and external experts.

Regional cooperation among the UKOTs and with neighboring Caribbean nations has strengthened conservation outcomes. Sea turtles’ migratory nature means that effective protection requires coordinated action across their range. UKOTs participate in regional initiatives like the Wider Caribbean Sea Turtle Conservation Network (WIDECAST), sharing knowledge and aligning conservation strategies.

Turks and Caicos Islands & British Virgin Islands

The Turks and Caicos Islands (TCI) provides an instructive case study in the evolution of turtle conservation policy. Historically, TCI had a traditional turtle fishery with minimal regulation. Recognizing the need for sustainable management, the territory engaged in a participatory process to develop new regulations.

Working with the Marine Conservation Society, TCI used the Community Voice Method to gather perspectives from fishers, conservation groups, tourism operators, and other stakeholders. This inclusive approach built support for regulatory changes enacted in 2014, which prohibited taking of large, reproductively valuable turtles while allowing limited traditional harvest of smaller juveniles.

Ongoing monitoring in TCI assesses the effectiveness of these regulations, with early indications suggesting positive population responses. This adaptive management approach exemplifies how conservation measures can accommodate traditional practices while ensuring population sustainability.

The British Virgin Islands (BVI) offers another valuable case study, focused on rebuilding turtle protection following devastating hurricane impacts. After Hurricane Irma in 2017 caused massive damage to marine habitats and conservation infrastructure, a Darwin Plus-funded project helped restore monitoring capabilities and develop a Turtle Recovery Action Plan.

This BVI project combines scientific assessment of turtle populations and habitats with community engagement to establish conservation priorities. The resulting action plan addresses both immediate recovery needs and longer-term conservation goals, including recommendations for legislative updates to strengthen turtle protection.

Both case studies demonstrate how UK support—financial, technical, and legal—can enhance local conservation capacity in the UKOTs while respecting territorial autonomy. They also illustrate the value of participatory approaches that build local ownership of conservation initiatives, creating more sustainable outcomes than top-down interventions.

Enforcement and Compliance

Enforcement of turtle protection laws in the UK involves multiple agencies, including marine police units, fisheries authorities, conservation bodies, and border control agencies. This multi-agency approach addresses the diverse nature of potential violations, from accidental bycatch to deliberate targeting or illegal trade.

In UK territorial waters, enforcement primarily falls to marine police units and the Marine Management Organisation (MMO), which monitor compliance with wildlife protection laws. These agencies conduct regular patrols, respond to reported violations, and investigate suspected offenses against protected species including sea turtles.

At borders and ports, UK Border Force has responsibility for preventing illegal wildlife trade, including turtle products prohibited under CITES regulations. Specialized wildlife crime officers receive training in identifying turtle products and documents, enhancing detection capabilities.

Compliance promotion forms an important complement to enforcement activities. Educational initiatives targeting key stakeholder groups—such as fishing communities, shipping operators, and coastal tourism businesses—aim to increase awareness of turtle protection laws and encourage voluntary compliance.

Penalties for violations can be substantial, with fines of up to £5,000 per offense for most violations under the Wildlife and Countryside Act, and up to £20,000 for offenses affecting Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Corporate entities can face higher penalties, and responsible individuals within organizations may also bear personal liability.

Despite these provisions, enforcement in practice faces several challenges. The vast marine area under UK jurisdiction makes comprehensive monitoring impractical, and the migratory nature of sea turtles means that threats often transcend jurisdictional boundaries. These challenges underscore the importance of international cooperation in enforcement efforts.

Future Challenges and Opportunities

Climate Change Impacts

Climate change poses perhaps the most pervasive threat to sea turtles globally, with impacts that will affect UK conservation efforts both domestically and in the Overseas Territories. Rising temperatures, changing ocean conditions, and increased storm activity all create new challenges for turtle protection.

Sea level rise threatens nesting beaches, particularly in low-lying UK Overseas Territories. As beaches erode or become inundated, suitable nesting habitat may decrease, forcing turtles to use suboptimal sites or abandon traditional nesting areas altogether. Beach replenishment or artificial barriers intended to protect human infrastructure may further reduce nesting habitat quality.

Temperature changes affect sea turtles in multiple ways. Most critically, the sex of turtle hatchlings is determined by the temperature at which eggs incubate, with warmer temperatures producing more females. Studies from some regions already show highly skewed sex ratios, raising concerns about future reproductive capacity.

Ocean acidification, another consequence of climate change, may impact the food sources that turtles depend on. Coral reefs—critical feeding grounds for hawksbill turtles—are particularly vulnerable to acidification and warming, potentially reducing prey availability for turtles in UK Overseas Territories.

Changes in ocean currents could alter the dispersal patterns of hatchlings and juveniles, potentially disrupting established migratory routes. For UK waters, shifting currents might change the frequency and distribution of turtle occurrences, necessitating adaptations in monitoring and protection strategies.

More positively, climate change awareness has created new opportunities for integrating turtle conservation into broader climate resilience initiatives. Programs promoting coastal habitat protection as natural sea defenses can simultaneously benefit turtle nesting beaches. Similarly, reductions in carbon emissions benefit turtles while addressing climate change’s root causes.

Post-Brexit Conservation Policy

The UK’s exit from the European Union has created both challenges and opportunities for environmental protection, including sea turtle conservation. Brexit necessitated the creation of new domestic legislation to replace EU regulations, a process that has maintained substantive protections while creating new implementation mechanisms.

The Environment Act 2021 establishes a new framework for environmental governance in the UK post-Brexit. This includes the creation of the Office for Environmental Protection (OEP), an independent watchdog to hold government and public bodies accountable for environmental obligations, potentially strengthening enforcement of wildlife protection laws.

For sea turtles specifically, the UK has maintained protections equivalent to those previously derived from EU directives. The Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2017 and the Conservation of Offshore Marine Habitats and Species Regulations 2017 effectively transpose former EU protections into domestic law, ensuring continuity of protection.

Brexit also offers opportunities for the UK to develop more tailored approaches to marine conservation. The UK Marine Strategy, which sets out the government’s approach to achieving clean, healthy, and biologically diverse seas, can now evolve independently of EU frameworks, potentially allowing more responsive adaptation to emerging conservation challenges.

In international forums, the UK has maintained active engagement on marine conservation issues post-Brexit. Continued participation in international agreements like the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS) and CITES ensures that the UK remains integrated into global conservation efforts for highly migratory species like sea turtles.

For UK Overseas Territories, Brexit has limited impact on turtle conservation directly, as these territories were never part of the EU. However, changes to UK funding mechanisms and priorities could affect support for UKOT conservation initiatives. The government has committed to maintaining environmental funding through programs like Darwin Plus, but long-term arrangements remain to be fully established.

International Collaboration

Sea turtles’ highly migratory nature makes international collaboration essential for effective conservation. The UK participates in numerous multilateral frameworks addressing turtle protection, complementing domestic legislation with coordinated international action.

The Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS) provides a global framework for conserving migratory species including sea turtles. Through this convention, the UK collaborates with other range states to develop coordinated conservation strategies that address threats throughout turtles’ migratory routes.

Regional instruments like the Protocol Concerning Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife (SPAW Protocol) to the Cartagena Convention address marine conservation in the Wider Caribbean Region, including several UK Overseas Territories. This framework facilitates regional cooperation on habitat protection, species management, and capacity building.

Research collaboration represents another dimension of international cooperation. UK-based institutions partner with organizations worldwide on turtle research, from satellite tracking studies revealing migration patterns to genetic analyses identifying population structures. These collaborative efforts produce knowledge that informs conservation strategies across jurisdictional boundaries.

Capacity building in developing countries constitutes an important aspect of the UK’s international turtle conservation engagement. Programs funded through UK aid mechanisms support training, equipment provision, and institutional development in countries that share turtle populations with the UK and its territories.

Looking forward, enhanced international collaboration will be essential for addressing emerging threats to sea turtles. Issues like marine plastic pollution, climate change impacts, and fisheries bycatch require coordinated multinational responses. The UK’s established diplomacy networks and scientific expertise position it to contribute significantly to these collaborative efforts.

Conclusion: Strengthening the Legal Shields

The UK’s legal framework for sea turtle protection, while robust, requires ongoing strengthening to address evolving threats and fill existing gaps. Several opportunities exist for enhancing the effectiveness of these legal shields for endangered turtle populations.

First, domestic legislation could be updated to more explicitly address emerging threats like plastic pollution and climate change impacts. While existing laws protect turtles from direct harm, they less comprehensively address indirect threats that may ultimately prove more significant for population viability.

Second, enforcement capacity could be enhanced, particularly in offshore waters and Overseas Territories where monitoring coverage is often limited. Increased resources for patrol vessels, training programs for enforcement personnel, and new technologies like satellite monitoring could all strengthen implementation of existing protections.

Third, the coordination between legislation covering different jurisdictional zones—territorial waters, offshore regions, and Overseas Territories—could be improved to ensure consistent protection throughout turtles’ ranges. Current arrangements, while comprehensive, sometimes create complexity that challenges effective implementation.

Fourth, incorporating traditional ecological knowledge and cultural perspectives, particularly in Overseas Territories with historical connections to turtles, could enhance both the effectiveness and legitimacy of conservation measures. The success of participatory approaches in territories like the Turks and Caicos Islands demonstrates the value of inclusive policy development.

Fifth, strengthening the legal framework for protecting migratory corridors and foraging grounds, not just nesting beaches, would better reflect the ecological needs of sea turtles throughout their life cycles. Current protections tend to focus more intensively on nesting areas, which represent only a small portion of turtles’ habitat requirements.

Finally, ensuring adequate post-Brexit funding for conservation initiatives, both domestically and in Overseas Territories, will be essential for maintaining and enhancing protection efforts. Legal protections, however strong on paper, require resources for effective implementation.

The UK’s commitment to sea turtle conservation reflects both ecological understanding and ethical responsibility toward endangered species. By continuing to strengthen and adapt its legal shields for these ancient mariners, the UK can make a significant contribution to global efforts to ensure sea turtles survive and thrive for future generations.

Overview and Recommendations

This article has examined the complex web of legislation, regulations, and international agreements that collectively protect sea turtles in UK waters and Overseas Territories. From cornerstone domestic legislation like the Wildlife and Countryside Act to international frameworks like CITES, these legal instruments form overlapping shields against diverse threats facing turtle populations.

Several key themes emerge from this analysis. First, the transboundary nature of sea turtle conservation necessitates multilevel governance approaches that coordinate protection across jurisdictions. Second, effective conservation requires addressing both direct threats like hunting or bycatch and indirect pressures like habitat degradation or climate change. Third, legal protections, while essential, must be complemented by education, community engagement, and voluntary best practices to achieve conservation goals.

Based on these insights, we offer the following recommendations for strengthening sea turtle protection under British jurisdiction:

- Enhance monitoring programs in both UK waters and Overseas Territories to better understand turtle distribution, abundance, and threats. Expanded citizen science initiatives could supplement professional research efforts.

- Increase funding for enforcement of existing protection measures, particularly in remote areas where illegal activities may go undetected. This could include investments in new technologies like drone surveillance or satellite monitoring.

- Develop more explicit climate adaptation strategies for turtle conservation, including identifying and protecting potential future nesting beaches as sea levels rise and temperatures change.

- Strengthen measures to reduce bycatch in commercial and recreational fisheries, potentially including seasonal fishing restrictions in areas of high turtle concentration.

- Expand marine protected areas to encompass key turtle habitats, migration corridors, and feeding grounds, not just nesting beaches.

- Increase support for rehabilitation facilities capable of treating injured or cold-stunned turtles found in UK waters.

- Further integrate turtle conservation with marine litter reduction efforts, recognizing the particular threat that plastic pollution poses to these species.

- Develop standardized protocols for coastal development in UK Overseas Territories to minimize impacts on turtle nesting beaches.

- Enhance coordination between UK government departments with responsibilities relevant to turtle conservation, including environment, fisheries, international development, and foreign affairs.

- Support research on emerging threats like contaminants, underwater noise pollution, and disease, updating protection measures as new evidence emerges.

By implementing these recommendations, the UK can build upon its existing commitment to sea turtle conservation and strengthen the legal shields that protect these endangered species. As global biodiversity faces unprecedented pressures, the fate of iconic species like sea turtles will increasingly depend on robust legal frameworks, effective international cooperation, and sustained political will for conservation action.

The UK, with its combination of domestic waters hosting foraging turtles and Overseas Territories supporting nesting populations, has both the responsibility and the opportunity to play a leading role in global efforts to secure a future for these remarkable marine reptiles.